John Woodrow Cox describes the widespread impact of gun violence on children, and says change is still possible

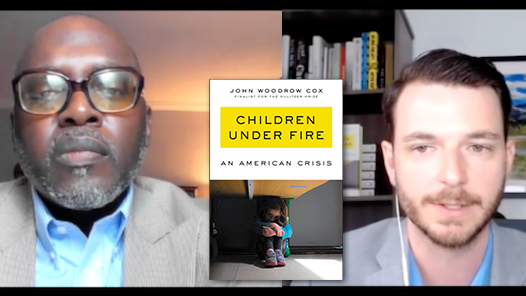

Watch our online Book Chat with John Woodrow Cox

Ava was a first grader when her best friend Jacob was shot on their playground at school. “Ava adored Jacob. She envisioned marrying him when they got older,” said author John Woodrow Cox in a recent online book chat with Goddard Riverside’s Chad Franklin. “She was devastated—she is devastated.”

Tyshaun was in the first grade too when his father was shot. The two children’s backgrounds are different—he’s black, from a Southeast DC block where gun violence is commonplace; she is white and from a tiny South Carolina town. But they struggled in similar ways after the shootings. Tyshaun had outbursts at school, once flipping over a desk, and another time shoving a fellow student into the wall. Ava had periods of white-hot rage. “She began to harm herself, she would dig her nails into her ellbow and pull out her eyelashes and bang her head against the wall,” Cox recounted.

Both of these children had their lives torn apart. But they have another thing in common: they were not seen as victims of gun violence by law or popular opinion.

“The scope of this problem is so much larger than Americans realize,” Cox explained. “We look at the 45,000 people who died last year in shootings—it’s a staggering number, but it doesn’t come close to the number of people affected.”

That number is in the millions, Cox said, and young people are particularly vulnerable—even if they don’t lose a loved one. He cited a Chicago study of children who lived in neighborhoods where a gun homicide had occurred. It found that the violence had an immediate impact on their school performance: “They didn’t have to know the person, they didn’t have to see it or hear it, they just had to know someone in their neighborhood was shot to death—and it affected how well they did on their test scores the following week.”

Cox is a reporter at the Washington Post. He won our Goddard Riverside Stephan Russo Book Prize for Social Justice last year with his first book, Children Under Fire: An American Crisis.

Far more children should receive support when they’re touched by gun violence, Cox argued—and the amount of support should not vary according to the child’s background. He pointed out that when there’s a shooting at a majority-white school in the suburbs, resources come flooding in. But shootings in poorer Black and brown neighborhoods get overlooked. “There’s a belief that says it’s just the way it is for those kids, because they live in this zip code, because of the color of their skin,” he said. “It’s a lie. And it’s racism. I don’t know any other way to describe it.”

A few changes in the law could make a big difference, he added. We can stem the flood of guns across the country by requiring a background check for every gun purchase. We can help keep them out of the hands of children by passing tough laws requiring parents to secure them at home. Small and inexpensive safes are now available that can be opened in seconds in an emergency, he explained: “There is no excuse to have a gun in a bedside table.”

While the human cost of gun violence is overwhelming, Cox holds out hope that the end is in sight. He says grassroots groups like Moms Demand Action are increasingly effective at shaping public opinion and pressuring Congress. Meanwhile, young people like the Parkland survivors who formed March for Our Lives are poised to shake things up.

“This whole generation of kids who’ve grown up cowering in their hallways and thinking they might die in school—they’re going to be voters and they’re going to be lawmakers and leaders, and I don’t think they’re going to allow that culture to continue,” he concluded.

“There is hope. And I think young people in particular are the ones who are going to change things.”